Most of the partygoers looked to be in their early and mid 20s, just like I was the first time I came to this exact spot nearly 12 years ago, back when it was a tiny indie rock bar called Kinky. Standing here now, I could almost see myself as I was then: a 24-year-old backpacker sitting alone in the corner, smoking cheap Greek cigarettes and nursing a raki, unaware that my life had come to a crossroads.

There are places we live and places we visit, and then there are the other places. Places we return to, where we put down roots, but not strong enough roots to hold us — places that change us, that we haunt and are haunted by. Nowhere embodies this for me more than Athens, a city I’ve watched shift and evolve, endure crisis and chaos and economic collapse, and yet emerge from the wreckage as one of the continent’s most vibrant and significant cultural capitals, more popular than ever as a tourist destination. (Last year Athens welcomed a record 5 million visitors, double the 2012 figure.)

|

| Restaurants, clubs and bars like Baba au Rum, above, have energized the night life scene in Athens. |

The first time I came here, I was more or less fleeing New York. I had saved up a chunk of money bartending after college at one of those high-volume, pre-crash Soho bars that catered to young Wall Street types. Being a Midwesterner with no connections or career prospects to speak of, I had done what countless other young Americans did before me: I bought a backpack and a one-way ticket to Europe.

After a week or so bouncing around the Cyclades, I arrived in Athens, planning to stay only a few days before moving on. People had told me the city was ugly and congested, basically a stopover, yet I remember the first romance of its winding, cracked stone alleyways overgrown with jasmine creepers and bitter orange trees, the roving packs of stray dogs, cats sunning on ruins, the smell of leather, honeysuckle and dust.

One night I wandered into Kinky Bar, where the D.J. was playing obscure postpunk records I happened to love. I drank until I was brave enough to approach him. He introduced me to his friends — Athenians, a bit older than I was — and at the end of the night, they did something I couldn’t imagine happening back home: They invited me to move in with them.

They all lived on or near a small, leafy street called Semitelou on a hill near the Athens Music Hall. Over the next weeks, I lived between their apartments, typical residential buildings with wraparound balconies and sun-bleached awnings that faced each other over the street. They were journalists, D.J.s and architects. Two were identical twin brothers, one gay and one straight. They lived with the straight twin’s girlfriend, a biologist who traveled with a suitcase of human sperm samples.

|

| The Breeder gallery has helped bring international attention to Greek talent. |

They showed me the city, its chaotic cafes and dusky tavernas. We packed into the car they all shared and drove around the gasworks of the Gazi district in search of after-hours bouzouki bars, saw concerts in Orthodox churches, prepared huge home-cooked dinners that we washed down with wine and vodka and other substances of varying toxicity and legality.

“It’s like the show ‘Friends’ but with sex, drugs and balconies,” I wrote at the time in my journal. It was a period in my life when I kept one rigorously, documenting nearly every romantic and philosophical quandary, every insight, not least of which was my decision to stay abroad and try to write professionally.

I loved Athens but wanted to see more of Europe, and it was my Athenian friends who directed me to Berlin, somewhere I’d had no desire to visit, but where I would end up spending the next decade, settling down, becoming a writer, meeting my husband.

I returned to Athens with some frequency at first, but eventually my friends and I fell out of touch, just at the time their lives were growing increasingly difficult. The downgrading of Greece’s credit rating in 2009 kicked off a series of tough austerity measures that crippled the economy. “We are trying to be O.K. in this sinking country,” one friend wrote in an email in 2011. Like the rest of the world, I watched most of it from afar: shutdowns, riots, civil unrest, mass unemployment, deepening recession.

|

| Nolan, which has a Greek-Japanese menu, is among the many inventive restaurants that have opened in recent years. |

How, then, to explain the Athens I find now, returning in the flush of spring with my old journals to reconnect with the city of my recollections? The commercial center, which I remember going dark at the end of the work day, was overflowing with visitors and locals, patronizing stylish, next-generation bars, cafes and restaurants that have largely deposed the cheap souvlaki joints and outdated tavernas I remember.

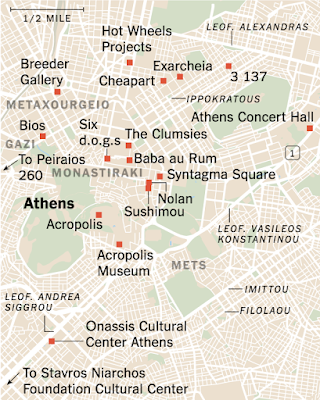

I ate soba noodles with chunks of smoked salmon in tahini broth at Nolan, a Japanese-Greek restaurant that opened in 2015 near Syntagma Square, then walked a block over to the 14-seat Sushimou where the sushi sourced from Greece has earned the chef Antonis Drakoularakos a spot on a list of the “100 Best Chefs in the World” by the French magazine Le Chef.

In just a handful of blocks, the same ones we used to traverse nightly between a few spirited dives, there are now dozens of nightspots, including two cocktail bars, The Clumsies and Baba au Rum, that have been ranked among the world’s best. Our old haunts are mostly gone, though as I passed the motley art-cafe, Booze Cooperativa, I was heartened to see the eccentric proprietor and septuagenarian local cult figure, Nikos Louvros, still holding his position out front, intrepidly smoking and drinking in the noon day sun.

Neighborhoods that were rundown and neglected have become seed beds for the arts, like Metaxougio, which not long ago was best known for its junk stores and Asian groceries, but now hosts the thriving multispace Bios and one of the city’s most important contemporary galleries, The Breeder, which has helped bring international attention to Greek talent like the painter Sofia Stevi and Stelios Faitakis, a street artist whose murals evoke Albrecht Dürer and Diego Rivera.

Then there are the major public arts institutions, which were either donated to the state by private philanthropic organizations or funded before the crisis, in part with foreign money: the spectacular, largely European Union-funded Acropolis Museum, opened in 2009, that rises next to the Acropolis like a glass-and-concrete mirror image; the Onassis Cultural Center, which opened in 2010 and encompasses two state-of-the-art performance halls, an open-air theater and an exhibition space; and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, a Renzo Piano-designed cultural complex, completed in 2016, some three miles down Siggrou Avenue from the Onassis Center on the Bay of Faliro. It includes facilities for the National Library of Greece, the Greek National Opera and a five-acre park, all of which the foundation donated to the Greek state.

The joke in town is that the most famous rivalry in modern Greek history — between Stavros Niarchos and Aristotle Onassis, shadowy shipping magnates who spent their lives feuding over business and romantic interests — now plays out along Siggrou Avenue and through the prolific cultural programming, grants, residencies and public works of their respective legacy foundations. Last year, among many other events, the Onassis Center staged its annual Fast Forward Festival, focused on techno-futurism and new media, a science fiction festival and an Afrofuturism series, which included a concert by the Sun Ra Arkestra with tickets as low as 5 euros. In the same year, the Niarchos Center made numerous high-profile performances entirely free to the public, including a Yo La Tengo concert and a presentation by the Shanghai Kunqu Opera Troupe.

In so many ways, Athens feels more alive, more culturally prolific, than ever, and it’s hard to understand how this could have happened in the midst of the worst economic catastrophe in the history of the European Union.

“It’s been interesting and hellish,” said Theodosis Michos, raising his voice over the music at the Six d.o.g.s. party. With his thick black-rimmed glasses and tattoos, his rake-thin build and wild, Richard Hell-esque hair, he looked exactly as I remembered him when I was staying at his place on Semitelou, give or take a decade of worry lines. Back in 2006, he was a staff writer for Esquire Greece, but like almost all the Greeks I know, the crisis left Theodosis out of work.

|

| The Clumsies bar in the city center is known for its creative cocktails. |

“We all got fired or we quit because we weren’t getting paid,” he said. And yet in 2013, arguably the lowest point of the crisis, Theodosis was part of a collective that launched Popaganda, an online magazine that covers culture and city life through an Athenian lens. “The first thing we did to resist the crisis psychologically was to tell ourselves again and again: O.K., we are artists, we are writers, this is the best time for us, because when artists have nothing, they can do anything,” he said, adding that this isn’t actually true. “We told ourselves this so many times, that we started to believe it.”

Even on a shoestring budget, Popaganda managed to establish itself as a platform on par with the city’s top culture magazines. Theodosis also wrote a novel, Take the Show, loosely based on the Semitelou years that’s been an indie hit (A bit character in the book is an American backpacker inexplicably living in their apartment).

“It’s not like oh, the crisis, I’ll start painting. That’s not happening!” said Konstantinos Dagritzikos, who opened Six d.o.g.s. with a partner, Panagiotis Pilafa, in 2009 in the space that used to hold Kinky Bar and four other venues. And yet the place they launched at the start of the crisis did evolve into the ambitious cultural venue they imagined, which now attracts droves to shows by Greek artists like the fuzz-rock outfit The Noise Figures and the chill-wave duo Keep Shelly In Athens, as well as international acts. This year, they’re launching an electronic music festival, ADD, which will bring artists like Apparat and Speedy J to Peiraios 260, a reclaimed 1970s-era furniture factory on the city’s outskirts.

The day after the party, I headed to Exarcheia, the graffiti-covered anarchist and student district that was the site of a scene I described in my 2006 journal, which now feels to me like an omen: “Saw a shop with a 10-foot hole bashed through the window, riot cops everywhere, employees crying.”

Less than two years after that entry, the neighborhood was the focal point of riots, triggered by the killing of a 15-year-old student by Athenian police, but thought to have deeper roots in growing frustration with the country’s economic and social dysfunction. The riots spread throughout Athens, then beyond into Thessaloniki and elsewhere in Europe, drawing many of the battle lines that would ossify once the Greek crisis erupted the following year. This widespread radicalization ultimately led to the election of Europe’s first left-wing government, the Syriza party, which came to office in 2015 on an anti-austerity platform.

Exarcheia remains a hub for anarchists, but the tatty graffiti I remember now accompanies a multicolored profusion of street art, evidence of the neighborhood’s emergence as a center for artists, who were drawn from Greece and abroad to the cheap rents, derelict spaces and unique cultural history. Galleries like Hot Wheels Projects and CHEAPART exhibit Greek and international artists, and Documenta 14 set up its headquarters here in 2017, the first time since its inception in 1955 that the international art exhibition took place (in part) outside the German city of Kassel. Though it didn’t come without controversy, including accusations of cultural colonialism, Documenta turned the scene into a topic of international import.

“I think Documenta accelerated something that was already going on,” said Kosmas Nikolaou, one of three artists behind 3137, an artist-run space that puts on several exhibitions a year, as well as performances, presentations and cultural talks. When 3137 moved into the neighborhood in 2011 it was the only one of its kind; now it’s one of many.

But it remains to be seen whether Documenta’s bolstering of the art scene will last. And despite recent talk of Athens being “the new Berlin,” the city still struggles with poverty, riots and drug crime, not to mention continued reverberations of the refugee crisis — something perhaps most visible in Exarchia, where many migrants from war-torn countries in Africa and the Middle East live in squats run by anarchists and activists.

|

| At Sushimou, the sushi is sourced from Greece; the restaurant’s chef, Antonis Drakoularakos, has earned a spot on a list of the “100 Best Chefs in the World” by the French magazine Le Chef. |

“You’re living in uncertainty all the time,” said Meropi Kokkini, another writer friend I stayed with back in 2006. I had come to meet her and George — her longtime partner who was the D.J. that first night at Kinky Bar — at a new poké bowl stand in the city center. I often stayed with George and Meropi when I visited Athens in the years after my first stay, sitting up all night talking and drinking until I had almost missed my flight — and on at least one occasion, actually had.

Like most everyone, Meropi and George struggled through the crisis years. Meropi spent a year unemployed before becoming a freelancer. “But then all the magazines I was writing for shut down,” she said. Now she’s working as a staff writer at Lifo.gr, one of Greece’s most popular websites, and soon to spend a month in New York on a Niarchos grant, but like everyone, she fears continued volatility.

As we spoke, people streamed by us in the cooling evening air, some dragging suitcases or holding phones open to Google Maps. “There’s a feeling now that things are getting better,” she added, “but I don’t know if it’s real.”

In the past year or two, Greece has shown signs of recovery. Unemployment, which peaked near 30 percent in 2013, is below 20 percent and falling, and the economy is growing faster than the European average. Much of this growth comes from the tourism sector as visitor numbers have surged, increasing for the past decade at around 11 percent per year, in part due to fears about turmoil in Turkey and the Middle East, as well as increased tourism from the newly wealthy Asian middle classes. The country expects a new all-time high of 32 million visitors in 2018, three times its population.

|

| Six d.o.g.s. is a cafe-bar and arts space that runs the length of an alleyway in the Monastiraki neighborhood. |

“It’s crazy, the tourists in recent years. It’s like the whole world is coming on vacation to Greece.” said Fotis Vallatos, the travel editor of Blue Magazine, the in-flight publication of Greece’s largest airline, Aegean Airlines, and a co-founder of Popaganda, as well as the person who first invited me to move in to Semitelou.

As tourism has increased, Aegean Airlines expanded from 18 mostly Greek destinations in 2001 to 145 all over the world today. Fotis is now often on the road, exploring those destinations and the many inventive restaurants and visitor attractions that have emerged in Greece since the crisis, from a wave of young chefs using Nordic, French and East Asian cooking techniques on local ingredients, to a multitude of “second-act producers,” people left unemployed or underemployed who returned to the villages where they grew up and began to sell homemade, organic, artisanal Greek products — to phenomenal results.

“I think everybody became more creative after the crisis, more cooperative,” he said.

We talked about the Semitelou days, how much fun it was to be so young and dumb. Back then, he said, “it was still a big party. We earned good money. We worked a lot, but it was a period when everybody was happy. We thought this party would last forever, and because of this, we lived that way. We never thought this might be over in a few years.”

Listening to Fotis, I realized that for my friends, even more than for me, those years must feel foreign — like a distant dream.

|

| The Booze Cooperativa bar survived the Greek debt crisis and remains a popular spot. |

As often happens when I’m in Athens, I was introduced to friends of friends and wound up in the hours just before I had to head to the airport at a party I didn’t want to leave. This one, though, was fancier than I was used to. It was thrown by Afroditi Panagiotakou, the director of culture for the Onassis Foundation. Formidable and eccentric in the way of Mediterranean aristocrats, she is the guiding force behind the foundation’s rebirth as an important engine of the city’s cultural scene.

“I have to say, I’ve never felt closer to this city,” said Afroditi, as we sat on the roof terrace of the villa she shares with her partner, Anthony S. Papadimitriou, president of the business and public benefit wing of the Onassis Foundation. We looked out over the Mets district, a palimpsest of red tile and concrete housing blocks behind which the Acropolis rises like a revelation.

“I think that Athens lies beyond good and evil, beyond beauty and ugliness,” she said. “I don’t think that cities are supposed to be beautiful anyway. I think they’re supposed to be interesting. They’re supposed to be alive. Athens is definitely alive. It doesn’t have this constipated, sclerotic thing that cities like New York, London, Paris have, where whatever you do, nobody will notice.” She added, “Athens is a city that is changing all the time.”

As we spoke, guests began to arrive — gallerists and producers, artists and writers on Onassis grants, mostly Greek but some Lebanese, part of the foundation’s effort to build more cultural exchange with the Middle East. Wine flowed and the music got louder, jumping from Bossa Nova to Italo-disco to Greek rebetiko as the sun began to set over Athens. By the time I left for the airport, nearly everyone was dancing.

Charly Wilder

Source: The New York Times

No comments:

Post a Comment